Uilleam’s

son Aodh [Hugh], the Fourth Mormaer of Ross, (born 1276) lived and died in a

manner that surely gratified the shades of his forefathers.

There

was renewed conflict with the English whose King Edward III was a far more determined man

than his father. The Battle of Halidon Hill (1333) was a horrible massacre.

Wikipedia sums up Aodh’s fate: “Scots honour was saved by the Earl of Ross and

his Highlanders, who fought to the death in a valiant rearguard action.”

His wife

Margaret Graham died the same year; if she still were alive at the time of the

battle, his fate wouldn’t have surprised her. For generations the main functions

of the Scots nobility had been to fight the English and to fight each other. I’ve

noticed our titled ancestors often were elderly when they led their clansmen

into battle, fully anticipating that death, not victory, awaited them.

Aodh’s

children soldiered on. His main heir was known as ”Uilleam de Ross, Fifth Mormaer

of Ross, Justicar of Scotia”. A daughter outdid this, becoming Queen Consort of

Scotland.

We are

descended from a “lesser” son, Jean de Ross. All we know about him is he

married the noblewoman Margaret Comyn and fathered a daughter Ena.

|

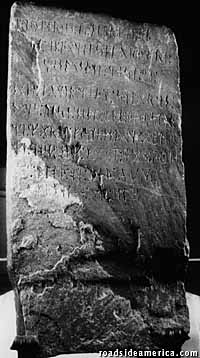

| The Kensington Rune Stone, found in Minnesota by a farmer, Olaf Ohlman in 1898. Source of the photo: Kensington Rune Stone Museum. |

Online

records hint at a very odd fate for Jean: ”died 3 December 1352 in Minnesota, USA”. Some gullible soul must have come up with this after watching

preposterous programs on the History Channel.

This place and date indicates our Jean was a Knight Templar (or a

Viking) on a secret mission to the New World accompanied by Sir William

Sinclair (right after he built Rosslyn Chapel) to secrete the Holy Grail. Or perhaps

it was the Ark of the Covenant, and/or establish an enormous land claim. He might have been traveling with (or captured by) a

band of itinerant Norse warriors and dropped dead after helping carve the Kensington

Rune Stone. And let us not exclude the possibility of abduction by a UFO…

Saner

suggestions have him dying in Scotland or England.